Magazine B No.61 ACNE STUDIOS

480.000₫

Cho phép đặt hàng trước

Founded in 1996 by Jonny Johansson and three partners, with only 10,000 euros, Acne was first launched as a small advertising and design agency in Stockholm. Acne, an abbreviation for “Ambition to Create Novel Expression,” is characterized as a creative collective that freely does whatever it wants, just as the name shows. One day, the company produced just 100 pairs of jeans to emerge as Stockholm’s representative denim brand. In 2006, Acne separated its fashion endeavors to create an independent brand called Acne Studios, and since then has consolidated its position as a major contemporary fashion house that crosses between the realms of fashion, culture and art.

Welcome to the 61st issue of B.

As a person who likes fashion, I enjoy staying on top of brand news and projects, as well as industry trends. I majored in fashion, and I also got my start at a fashion magazine, but there’s more to why I pay attention to the fashion industry. In my view, the industry is a barometer of sorts, its trends reliable clues to where broader lifestyle trends are headed. Whatever reputation fashion has, whether for capriciousness nor excessive showmanship, I feel no need to scorn it, or condemn it. The fashion world adapts to shifting terrain with a speed and agility that is rarely seen elsewhere. When changes present themselves in unexpected ways, the industry’s reaction is not to point fingers but rather to embrace such changes, and even transform and repackage them into attractive products. And all of this is done with enviable finesse. Having distinctive energy and readiness to adapt are key qualities major IT and retail players also appreciate, with more and more companies scouting fashion industry creatives for their teams.

In this edition, we introduce Acne Studios, a brand that has been at the forefront of change, not just in fashion but in the creative scene as a whole. Cofounder and creative director Jonny Johansson and his three founding partners were hardly typical entrants into the world of fashion. When they launched the label, Johansson was a 20-something from an outlying part of Sweden who dreamed of being a musician. His cofounders, like him, had a passion for design and the arts, and it was in the process of their collective creative experimentation that Acne was born. Their creative outlets had

mainly been digital art, lm, graphic design and branding, but on a whim, they decided to design jeans. There wasn’t any special reason, as Johansson himself recalls. The jeans were supposed to be a joke. The pink shopping bag and the brand’s unlikely name, though today Acne’s trademarks and held up as successful examples of intuitive branding, were decidedly unorthodox in the 1990s, when the brand made its debut. Yet two decades later, Acne boasts an ardent following for its unique culture that has formed around the faithfully expressed aesthetic instincts and tastes of its creators.

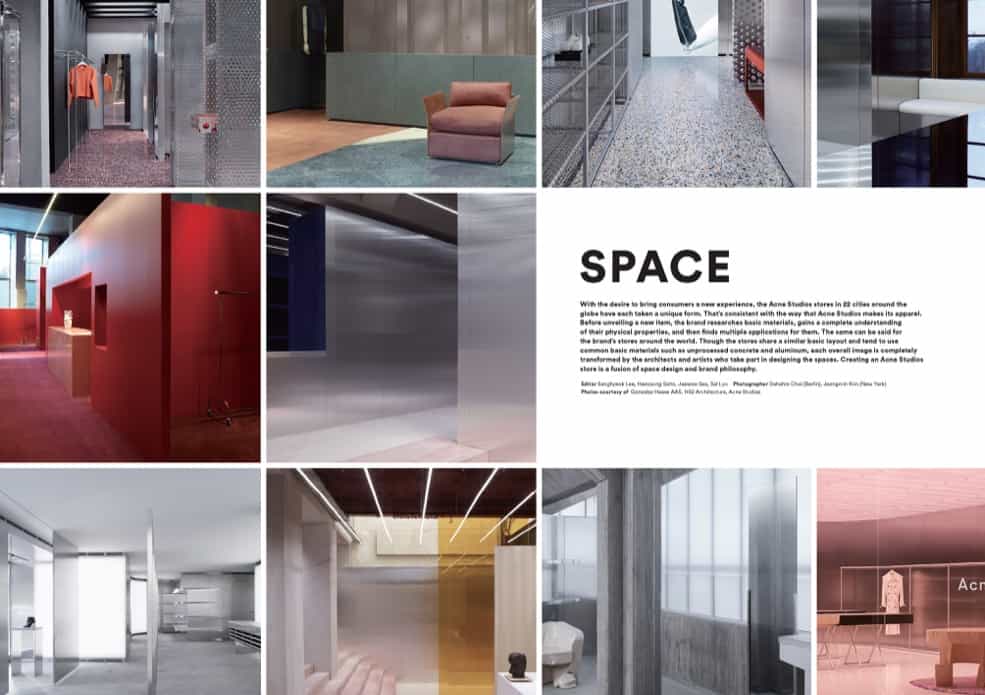

What makes Acne so appealing is different from what draws people to a brand like Maison Margiela, which we introduced in B last spring. Acne is a brand that designs clothing and yet strategically resists making clothing its sole medium for communication. In fact, sometimes its other endeavors get more attention – its flagship stores, as avant-garde as any gallery; its collaborations, not with celebrities or famous influencers but with artists; and Acne Paper, a platform for a wide array of content. Interestingly enough, the brand’s founders don’t deny this. In a past interview, Johansson explained that at Acne, concept is always first, and ideas are the main focus. If what he says is true, we might say that what Acne enthusiasts consume is not so much the products but the atmosphere surrounding them.

In 2016 alone, Acne Studios recorded 215 million dollars in revenue, almost twice the figure for the previous year. What’s more, this was achieved without acquisition of the brand by a luxury fashion house. Commercial success was garnered without rules and restrictions, and this was possible due to balance. Acne has mastered walking the line. It has fostered an eclectic, non-mainstream culture while showcasing product lines that satisfy even mainstream tastes. It finds an equally solid footing among high fashion brands as well as more casual contemporary makers. It is a Swedish brand markedly bare of the features that traditionally identify Swedish brands. Its minimalist designs are embellished with subtle maximalist details. And the signature pink of its packaging, once dismissed as helpless romanticism, has become the epitome of cool. This is a feat that perhaps only Acne, with all the things that make it what it is, could have pulled off.

I believe that this kind of Acne ethos will become increasingly visible across a range of business sectors. The boundaries that distinguish different types of creative work are dissolving at a rapid pace, and overlaps and ambiguities are no longer things

we question or find fault with. We are starting to approach fashion the way we would music, design the way we would cooking and films the way we would print magazines. In our day and age, no other philosophy is more appealing. There is a readiness to blend and blur, and to fell old boundaries, generating vast opportunities for a new age. I would venture that this same sense of possibility is what propelled Acne from a joke to where it is today.

Content & Editorial Director

Eunsung Park

Sản phẩm tương tự

📚 Có sẵn tại Sạp

Danh mục theo chủ đề

Danh mục theo chủ đề

Coffee & Café Culture (Văn hóa cà phê)

Danh mục theo chủ đề

📚 Có sẵn tại Sạp

📚 Có sẵn tại Sạp

Danh mục theo chủ đề