Magazine B No.31 DIPTYQUE

480.000₫

INTRO

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

COMMENTS

Some fragrant moments with Diptyque captured on Instagram

SURVEY

Lifestyle brand preference survey, with a focus on fragrances

MARKETS

Perfumes Perfume market brand positioning analysis

Scented Candles

Scented candle market brand positioning analysis

OPINION

Myrto Dimoula, a lover of scented products

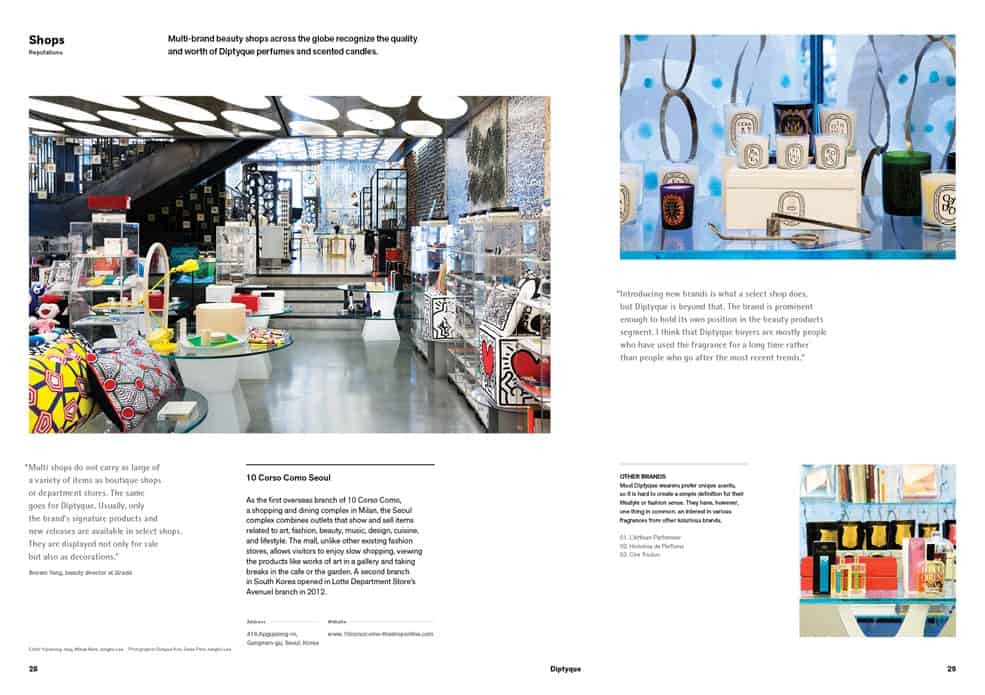

SHOPS

Reputations

Diptyque seen through the lens of concept stores that carry the brand

INNER SPACE

Lineup

Diptyque’s product lineup from scented candles to skin care products

Representations

Diptyque’s individuality revealed in its interpretations of candle fragrances

Design Language

Perfume brand vision as revealed in bottle and label design

OPINION

Kitae Kang, CEO of Maison des Bougies, a scented candle brand

RECOLLECTIONS

The special memories and objects recalled in Diptyque fragrances

OPINION

St.phane Jaulin, former beauty section director at the select shop Colette

INFLUENCE

Niche Startups

Boutique fragrance brands create new possibilities

LIFESTYLE

Scent Layering

Scent layering reveals the user’s individuality in diverse ways

B’S CUT

Capturing of Memories

Photo essay by photographer Marion Berrin

BRAND STORY

From the foundation by three artists as a small fabric boutique to becoming an iconic global fragrance brand

BEHIND THE DESIGN

Diptyque’s design language looked through six elements

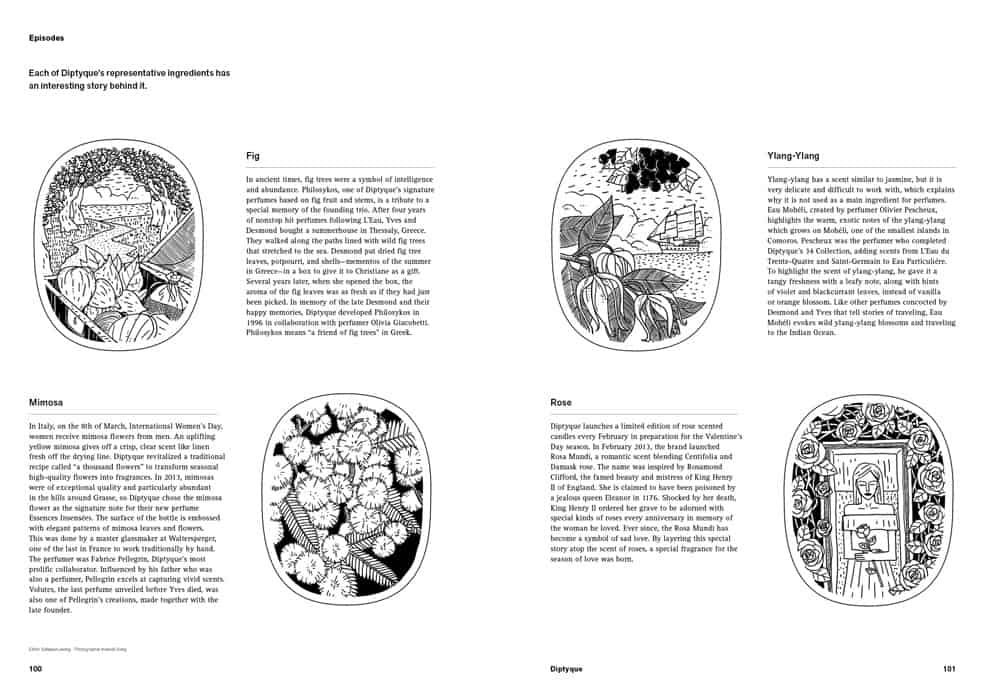

EPISODES

Some of the stories behind the development of Diptyque’s representative materials and products

CELEBRITY’S NOTES

Celebrity comments on Diptyque

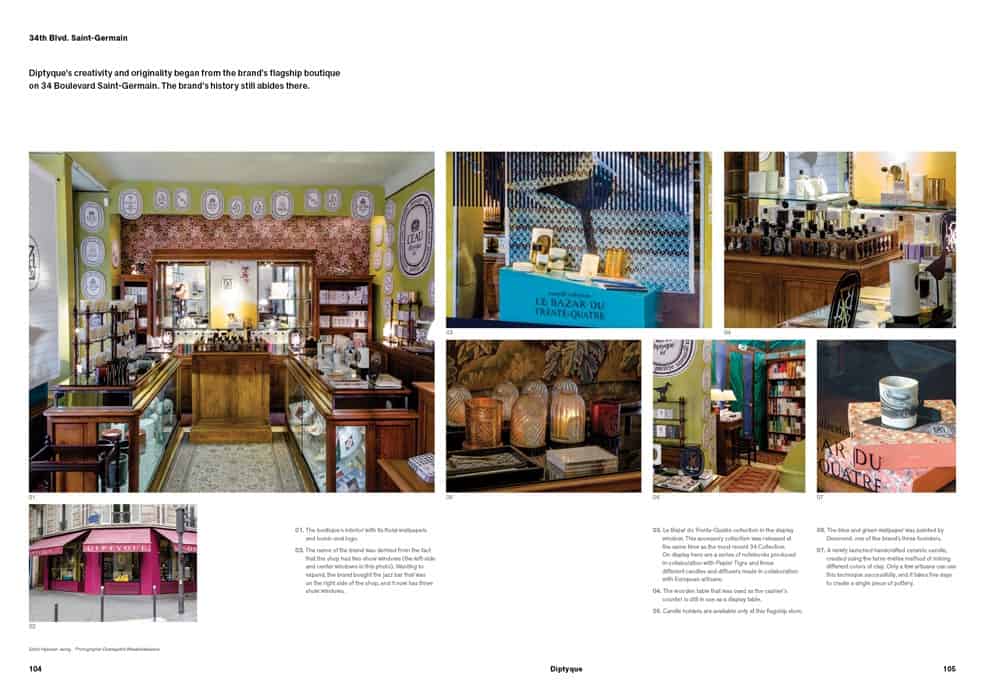

34TH BLVD. SAINT-GERMAIN

A visit to Diptyque’s flagship store

INTERVIEWS

Fabienne Mauny, Managing Director Myriam Badault, Marketing & Product Creation Director

FIGURES

The global scented product market and brand positioning

FACTS

Interesting Diptyque facts

FROM THE EDITOR IN CHIEF

Diptyque’s core values

OUTRO

Cho phép đặt hàng trước